What's in a price?

From the archives...

If economics is good for anything, one of its central tenants that has a simple and intuitive appeal is that the prices of things are usually fair in some sense. This is true if we accept demand and supply perform an endless magic dance, where the range of prices that people want to buy something, and the range of prices other people want to sell it, meet.

While a deliberate simplification, the point to register is we are told that competitive markets lead to prices that are in “equilibrium” because if the price was higher, there would be more things than people want, and if they were lower more people would want them than other people are willing to sell them. Every good or service will therefore have its one price — the equilibrium price — and markets are said to clear.

To be fair to most economists, they don’t really believe this is . Most do, though, think this is a close enough approximation of reality to be useful. Hopefully after you read this article, you will agree this is untrue for many of the prices we face. This is because for that nice story of demand and supply to work, it requires a few important things to exist, that incresingly do not. Chief among them is sufficient competition.

Price is so fundamental to the predictions of economists that it underlies many of their biggest arguments of the past 100 years, such as the discrediting of communism and explaining repeated financial crises. It is important to understand that when economists talk of prices, they are thinking in broad terms about information. The magic of capitalism, they say, is that the near infinite quantities of information out there about what people like, what is plentiful or scarce, what is new or old, fun or boring: everything that needs to be known, in short, to ensure we allocate the planet’s resources well — be they the minerals in the ground, the next pound you spend or your time — is conveyed through price. But, and in economics there is always a but, if we leave everyone to it, prices do not work as the free marketers would wish. Left to its own devices, “free” markets can give very misleading signals for long periods of time.

The problem with complaining about prices, as with many other things that economics claims but day-to-day experience defies, is what alternative reality you are making comparisons against. This is important to clarify to ward off any interpration you may have that I think prices ought to be controlled.

Because prices are a fundamental currency of information, to replace the billions of decisions that may influence prices with a state-sanctioned number would require an information gathering and processing capability beyond even Jeff Bezos’s imagination. While our instinct at seeing a small bottle of water on sale for £3 in an airport is to make this a capital offence, trying to set the “right price” for everything in a modern economy that trades goods, services, other country’s money, imaginary futures and debt is, currently, impossible. We can’t even manage to cap gas prices properly.

While I do not advocate for specific price controls, I don’t think we should accept that more state intervention to make prices less outrageous is the first step towards socialist ruin. If a growing lack of sufficient competition is leaving the setting of prices firmly in the hands of companies and not the jig between companies and consumers as we’re told, then one obvious solution is to ensure greater competition and reduce the dominance of large businesses.

Can the price of something be wrong?

What should things cost might be a more moral than economic question. Economics has a view, of course (try and stop economists having a view). The price is what it is — the equilibrium of supply and demand. If you don’t want to pay the price, don’t. Another way of looking at it, though, can suggest what the “right” price ought to be. In a competitive market the price of something rarely get too divorced from how much is costs to produce. Businesses need to make a bit of profit, sure, but if they make a massive margin then other companies are supposed to spring into existence and offer consumers a better deal.

Why, then, does this soft-cover notebook cost £50 and why does this luggage tag (well, it hold’s a £29 Apple AirTag) cost an embarassing £399 (at time of writing, sold out)? Is it because it is fauve coloured? I think the simple answer is that rich people are morons. But for things we all buy, I believe there is an increasing amount of price manipulation which means the price is wrong because it’s higher than it would be if someone else had the chance to sell it to you for less.

I’ve observed three forms of pricing madness: first, situations where you are temporarily unable to shop around and monopoly power goes to shopkeepers heads; second, a phenomenon economics says shouldn’t happen where the same item is on sale for wildly different prices; and finally, deliberate confusion to make price comparison almost impossible.

Micro-monopolies

The drinks prices in restaurants, food at a festival, concert or theme park, airline bag pricing, car hire insurance, mobile phone roaming charges, a cup of tea on a train: these are all examples of things you might like, but were not the reason you chose to be where you are. I present the micro-monopoly:

A situation where a company has captured you for a period of time to sell you things at outrageous prices, but for things that are not the primary reason you visited, and where the time cost of establishing these prices before you visit is prohibitive.

The scale of this hit me recently when I unknowingly paid £1.95 for a small packet of salted peanuts (put aside for now the peculiar fact that in Britain you pay to ingest salt to make you want to drink more beer):

What was fascinating about this con was the contrivance between a company producing a faux-luxury nut and the pub industry to try to psychologically justify this extreme peanut-inflation. These were not salted peanuts, they were “salt crust” peanuts. Peanuts with the salt made wet before they add it so it dries looking like they were specially handprinted by angels.

It’s a new twist on an old idea: find a way to make something look new to justify a price increase. In this case dilution of sodium chloride and the use of a foil bag to make it look special. But the reality is they have put less nuts in the packet and charged you more for them. (The per nut cost, by way of comparison, is six times a packet of salted peanuts sold by Morissons.) But you didn’t go to the pub for nuts, and you don’t have to buy it. But if you do, you will be ripped off proportionally to the extent that if they inflated the the cost of the beer by the increase in the cost of some nuts in another pub, it would be roughly £8 a pint.

Another example is the sale of water. In airports especially, but also in train stations, and even by such trusted brands and Marks and Spencer, a bottle of water is deliberately increased in price relative to the price in their other shops. Yes, you read correctly: M&S charges you more for water in a train station than the high street because they know you didn’t go into the shop just for water (temporary monopoly is created) and that people going on long train journeys want water. And because the relative cost of a bottle of water compared to the search cost of trying other shops nearby means you will likely pay it.

Price dispersion

Undergraduates of economics are taught there can only be one cost of things. This idea is so important its even got a judicial sounding name: the Law of One Price. If the same thing in different places has a different price there has to be good reason (and so it cannot be deemed the same “thing”). It took a while for economists to accept this was obviously nonsense and then to study it properly. Turns out, as any normal person could have told you, this so-called “price dispersion” is sizeable, pervasive, and persistent.

There is strong theoretical reasoning and empirical evidence that much (and in some markets, most) of the observed dispersion stems from consumers’ costs of acquiring information. These “shoe-leather” costs are intuitively obvious — how much time do you want to devote to trying to find a cheaper biro? Keep in mind that things that are a relatively smaller part of your budget (like salt crusted peanuts) might bother you less that you are being ripped off, but for society as a whole, those slices of pure profit add up.

Economists assumed the internet would solve this “information problem” because your ability to search for a lower price was supercharged. Turns out it made no difference. The online the Law of One Price is egregiously violated. Even more crazy is that the reduction in the cost of searching for prices that the internet and before it, the phone, newspapers and so on created, can lead to more or less price dispersion, depending on the market environment. By way of an example, I present the Chocolonely Chocolate Bar:

So what, you might say. Only £1.25 difference between the top and the bottom. But in percentage terms it’s 45 per cent. If this was a £500 washing machine that would make it £725.

Shops know you will not invest a huge amount of time in building a strategy to find the cheapest Chocolonely Bar. They also know chocolate is often an impulse buy. Like this eye-level product placement by the “healthy food” shop, Souced. These are £1.80 for 50g. That is the equivalent of £6.48 for a large bar, by the way.

Price distortion

The third way that prices are being manipulated is the creation of deliberate confusion to make comparison effectively impossible. One really useful thing economics tells us, and by useful I mean obvious, is that when there is little competition (a few big firms dominate the market — pretty much everything these days it seems), they do not compete on price. Doing so is risky because if one firms starts the others might have to and then everyone will make less money or perhaps go under.

Here is an example of a typical way consumers are unable to make a sensible comparison, in this instance choosing an electricity provider. Here are just two options of hundreds:

To make a sensible comparison on just these two you need to:

have serious mental arithmetic chops, or the time and inclination to build a model, including the ability to factor numbers with three decimal places, in parallel;

understand how standing charges and unit rates work;

know how much electricity you will consume for the next two years, using kilowatt hours as the basis of measurement (and hence know the power consumption of your various uses of electricity);

be able to construct two cost models because the standing charge is different so you cannot compare the unit cost alone — (and only the knowledge of your future electricity use will be able to show a winner); and

have knowledge of the future wholesale cost of electricity for the next two years (and some assumptions of the future path of inflation would be great).

Which means comparison is impossible. (If you want a dual fuel tariff then it becomes exponentially more complicated.)

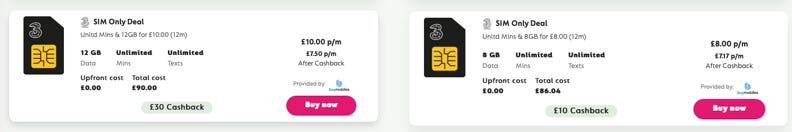

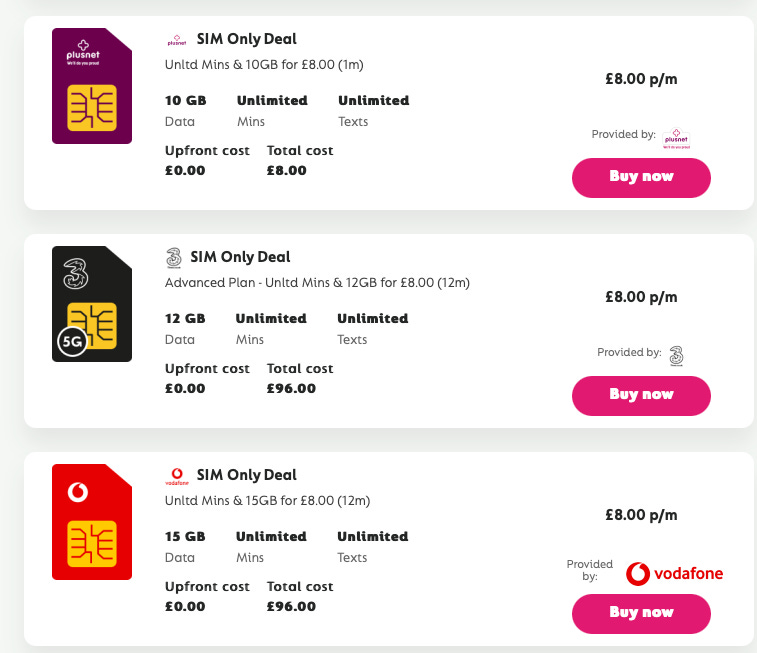

What about choosing a mobile phone contract? Putting to one side the minefield that is trying to extract the higher purchase payment plan that occurs if you also buy a handset and just trying to find the best “SIM only” deal. Imagine we want to choose Three (don’t, though, trust me) one price comparison site offers this:

The parasitical intermediary, who will be paid a fee by Three for getting your business, adds their own confusing bribe into this comparison. This shifts the relative prices from paying £2 extra a month for 4GB of more data to 33p extra. You still have to do some maths to show the shift:

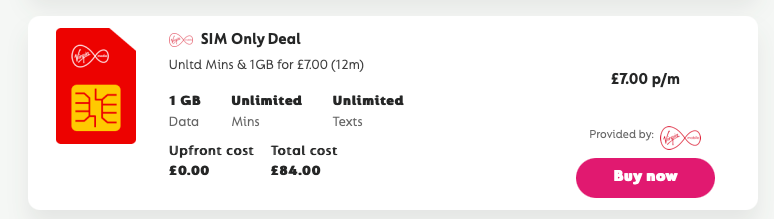

Looking more widely at what’s on offer, sense really starts to disintegrate. For example, would you rather pay £7 a month for 1 GB of data from Virgin Mobile;

or pay £7 a month for 4 GBs of data from Virgin Mobile?

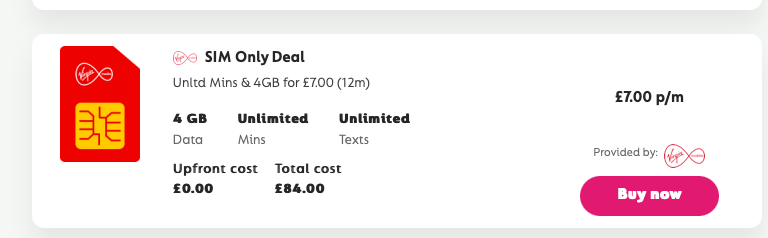

Say you want to pay £8 a month — any clearer? Depends. You can have 10 GB, 12 GB or 15GB. Your choice then becomes which company, and trying to work out what the speed, quality, coverage, service levels are like for each. Again, impossible.

These were only comparisons with unlimited calls and texts. Adding them into the mix and you would need to make a comparison along at least the following variables:

network reputation, coverage and speed;

data volume;

call and text allowance;

contract length;

strange additions like being able to roll over minutes; and

whether you get free EU roaming or not (most likely not).

Thats at least 9 variables to compare across, 3 or 4 options which would be vastly helped if you can cogitate matrices in your brain as well as knowing your preferences for all of these options, in order to optimise your choice.

The companies will, of course, say they are merely providing you with the tools with which to pick your perfect tariff. Choice is a good thing. But I think it is more likely they are deliberately confusing you to the point where you will never know if you have made a good choice.

So what?

My contention is the market is failing. Companies are obfuscating prices to make more money through, what is in effect, dishonest means. We are seeing this happen, too, through the novel methods of shrinkflation where prices don’t change but volume does in ways that make value for money comparisons mind boggling.

This limits your ability to make reasoned decisions and it is possible because there is insufficient competition. But should you care? You’re too busy to shop around, these are often small amounts of money and how could we ever hope to solve this if we’re agreed intervening to fix prices is a fools errand?

The country should care because from the perspective of society overcharging people is not efficient. The world would be a better place if there were more competition. But competition is often limited by the structure of the market. It is just more efficient to have one railway than several. So what’s to be done?

The government could take a deeper interest in how firms are setting prices and where profits seem out of whack. They do now and then, like the mild intervention to stop rip-off Covid testing. But if you were a minister would you want to start to annoy the five big companies who you are probably on good golfing terms with, and then put in the hard work of convincing your party to find legislative time, challenging the incumbent firms’ well funded communications strategy that shows them to be ethical, caring companies, and waste the opportunity cost of whatever else you could have spent your political capital on instead, for the chance it might reduce prices somewhat for the millions of people who probably don’t know they’re being ripped off? Probably not.