The Lesser Known Parts of the Diary of Samuel Pepys

You may have heard of Samuel Pepys, he of the diary fame. He lived in the seventeenth century and witnessed a load of history and, luckily for historians, kept a diary nearly every day for nine years. He lived through the fire of London, a plague or two, a civil war and even saw the monarch being executed in 1649 aged 15. But the less important parts of his diary are actually some of the most interesting. What follows, therefore, are the highlights of the lesser known parts of his diary.

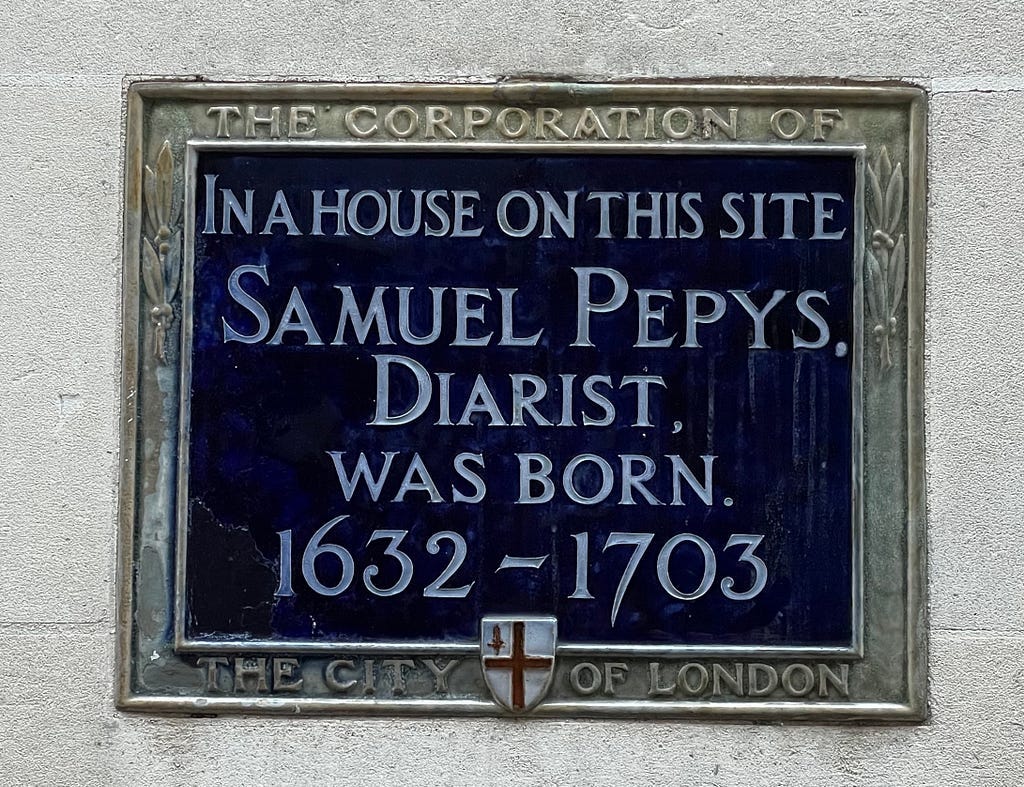

Samuel was probably born in London on the 23 February 1633, the fifth of eleven children, although by the time he was seven only three of his siblings, all younger, had survived. He was sent to grammar school at Huntingdon during the English Civil War (1642–1651). Like most senior civil servants today, he went to Cambridge where he attended Trinity Hall and then Magdalene colleges. It’s fair to say he wasn’t poor. He was also something of a lad. In 1653 the Registrar of Magdalene College noted that “Peapys and Hind were solemnly admonished by myself and Mr. Hill, for having been scandalously over-served with drink ye night before.”

He had, as will be seen, a curious relationship with his wife who, while he portrays her as quite the jealous nag, was more likely long-suffering given his passion for other women. A typical entry runs roughly thus:

Women

Sam like the ladies. He was married but had a curious relationship with his long suffering wife who he spent a lot of pages complaining about how annoyed she was:

“She was out of humour all the evening, and I vexed at her for it, and she did not rest almost all the night, so as in the night I was forced; to take her and hug her to put her to rest.”

His creepy desire for some women led him to follow them around, especially down alleyways. He had affairs and set out, in his own coded writing in case anyone found his diary, the anguish this caused him (I’d say not that much). Still, it didn’t stop him.

His language for the opposite sex was rather direct at times:

“We sat in an upper box, and the jade Nell come and sat in the next box; a bold merry slut, who lay laughing there upon people.”

Samuel’s prose could often be quite wordy, but that he liked looking at hot women can’t be fully hidden in the verbiage:

“She hath hired a chambermaid; but she, after many commendations, told me that she had one great fault, and that was, that she was very handsome, at which I made nothing, but let her go on; but many times to-night she took occasion to discourse of her handsomeness, and the danger she was in by taking her, and that she did doubt yet whether it would be fit for her, to take her. But I did assure her of my resolutions to have nothing to do with her maids, but in myself I was glad to have the content to have a handsome one to look on.”

He spent a lot of time looking at his young female staff, and was quite the critic:

“She is a mighty proper maid, and pretty comely, but so so; but hath a most pleasing tone of voice, and speaks handsomely, but hath most great hands, and I believe ugly; but very well dressed, and good clothes, and the maid I believe will please me well enough.”

His wife was always jealous, for good reason, and more than once downgraded or sacked their staff to limit their appeal to horny husbands. Sam, though, was often very noble and didn’t make a fuss:

“But in [my wife’s] fit she did tell me what vexed me all the night, that this had put her upon putting off her handsome maid and hiring another that was full of the small pox, which did mightily vex me, though I said nothing, and do still.”

He never missed an opportunity to find ways to spend time with different women, even those he felt were potentially not quite right:

“Upon my proposing it, [she] was very willing to go, for [she] is a whore, that is certain, but a very brave and comely one.”

Finally, it’s worth noting that upper class philandering seemed to be fairly en vogue at the time. For instance:

“He is certain that the Duke of Buckingham had been with his wenches all the time that he was absent, which was all the last week, nobody knowing where he was.”

Theatre

There was no Netflix during the English Civil War, not even Radio 4, so those that could afford to spent a lot of time at the theatre. Samuel was quite the critic and, a man after my own heart, found most plays he watched to be fairly terrible. Pity Shakespeare:

“Thence to the Duke of York’s house, and saw “Twelfth Night,” as it is now revived; but, I think, one of the weakest plays that ever I saw on the stage.”

And pity the young:

“Took my wife by a hackney to the King’s playhouse, and saw “The Coxcomb,” the first time acted, but an old play, and a silly one, being acted only by the young people.”

Mundane moments

Some of the most interesting parts of the diary are the mentions of everyday life. For example, can you remember your first ever glass of orange juice? Did you worry about its effect?

“Here, which I never did before, I drank a glass, of a pint, I believe, at one draught, of the juice of oranges, it is very fine drink; but, it being new, I was doubtful whether it might not do me hurt.”

Maybe he had just cleaned his teeth.

Entertainment was harder to come by. You had to make the most of what you had. In this example, Sam decides to take his wife to marvel at an overgrown lady:

“So to my wife, […] and in our way home did shew her the tall woman in Holborne, which I have seen before; and I measured her, and she is, without shoes, just six feet five inches high, and they say not above twenty-one years old.”

Pepys was also quite the tech nerd of his day. He records on 13 January 1669 that:

“This day come home the instrument I have so long longed for, the Parallelogram.”

This nifty device enables one to draw around an object and magically enlarge it perfectly on another piece of paper. Remember, there wasn’t much else to do.

Nothing was too mundane for his diary. It was, for example, a notable enough event for Samuel to move his table once every eight years that he noted:

“At the Office all the morning, and this day, the first time, did alter my side of the table, after above eight years sitting on that next the fire.”

Sam reminds us that hygiene has moved on somewhat in the past 400 years:

“So to my wife’s chamber, and there supped, and got her cut my hair and look my shirt, for I have itched mightily these 6 or 7 days, and when all comes to all she finds that I am lousy, having found in my head and body about twenty lice, little and great, which I wonder at, being more than I have had I believe these 20 years.”

London

Samuel lived very close to modern day Downing Street and spent a lot of time going up and down the river and gadding about town. London was as lively then as it is today:

“Going this afternoon through Smithfield, I did see a coach run over the coachman’s neck, and stand upon it, and yet the man rose up, and was well after it, which I thought a wonder.”

A wonder indeed. Building regulations were a work in progress:

“I passed by Guildhall, which is almost finished, and saw a poor labourer carried by, I think, dead with a fall, as many there are, I hear.”

And the capital has always not been everyone’s idea of fun:

“He also told us that he hath heard his father say, that in his time it was so rare for a country gentleman to come to London, that, when he did come, he used to make his will before he set out.”

Meow

Mr Pepys could be rather catty. He knew what he liked. Take art:

“We looked upon his picture of Cleopatra, which I went principally to see, being so much commended by my wife and aunt; but I find it a base copy of a good originall, that vexed me to hear so much commended.”

Or food:

“The dinner [was] not extraordinary at all, either for quantity or quality.”

“And there we did make a little meal, but so good as I never would desire to eat better meat while I live, only I would have cleaner dishes.”

Or other people’s children:

“Where, among other things, he tell me the first news that my [sister Jackson] is with child, and far gone, which I know not whether it did more trouble or please me, having no great care for my friends to have children.”

Or social decorum:

“My wife and I at church, our pew filled with Mrs. Backewell, and six more that she brought with her, which vexed me at her confidence.”

Sometimes he just didn’t hold back:

“Here Creed shewed me a copy of some propositions, which Bland and others, in the name of the Corporation of Tangier, did present to Norwood, for his opinion in, in order to the King’s service, which were drawn up very humbly, and were really good things; but his answer to them was in the most shitten proud, carping, insolent, and ironically-prophane stile, that ever I saw in my life, so as I shall never think the place can do well, while he is there.”

Sam’s character shines through his diary. He was witty, smart, modern and a little pretentious. But he was a decent enough bloke save a few marital missteps. He lived through some of the most important periods in our modern history and we’re grateful he had so much time on his hands to keep his write his massive diary. The abridged version is well worth a read not only to learn about actual history but what it was like to live in London 400 years ago.

The Lesser Known Parts of the Diary of Samuel Pepys was originally published in trenchantly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.